Setting Up a Pharmacovigilance System from Scratch

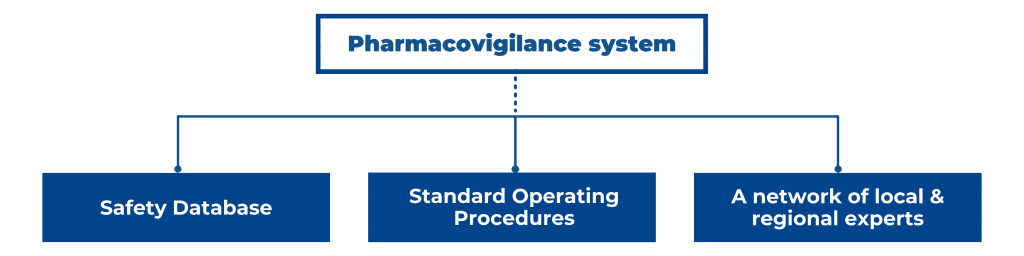

In the EU/EEA, US, and other major pharmaceutical markets, you need a sound plan for post-market surveillance for your medicinal product’s Market Authorization Application (MAA). A robust pharmacovigilance (PV) system consists of a safety database, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), a network of trained qualified persons in different regions, working with local regulators in local languages, and with regional regulators EMA, FDA, or MHRA. Therefore, a PV system requires considerable investments, which is not always attractive or feasible, especially for smaller pharmaceutical companies. If you are a pharmaceutical company that is marketing a new drug or accessing a new market, how to go about setting up a pharmacovigilance system for the EU/EEA, US, or even the global market? Furthermore, how do you ensure that you align your PV strategy with stringent regulations from the EMA or FDA? In this blog post, we discuss the function of a PV system, its core components, and the corresponding regulations and guidelines in the EU and US.

Keep in mind that this article describes the minimum requirements for any national PV system. It sets out what needs to be done as a minimum to ensure that a national PV system exists, and it can provide some measure of assurance for and security of medicines’ safety. Such a system is expected to be sustainable with guaranteed funding and a key focus on patient safety.

Why do you need to set up a pharmacovigilance system?

When a medicinal product gains Marketing Authorization Approval, its safety and efficacy have typically been examined through randomized clinical trials containing relatively homogenous patient populations in controlled clinical settings. The clinical trials stage is crucial as it provides evidence-based data related to the safety and efficacy of the product, but it leaves some gaps.

In clinical trials, the number of patients is limited, so rare ADRs may not be detected. Additionally, their duration is limited, and the possibility of missing ADRs developed after years is increased. Finally, usually special population groups (i.e., children, elderly, and pregnant/lactating women) are not involved in clinical trials.

Therefore, post-marketing surveillance of the medicinal product plays an essential role in discovering an undesirable effect that might present at risk and allows for long-term monitoring of the effects of drug products. Real-world settings include much more diverse patient groups, such as age, ethnicity and genetic background, dietary habits, pregnancy status, comorbidity and multi-drug use, and local clinical practices. Therefore, it is possible that adverse events of a medicinal product only occur in the ‘real world’ and were not seen in clinical trials or occurred so rarely that it is only detected in a substantial patient population. A recent example is the sporadic occurrence of thrombosis after administering certain Covid-19 vaccines, which has been detected through the PV systems after preliminary Marketing Authorization Approval.

How does a PV System work?

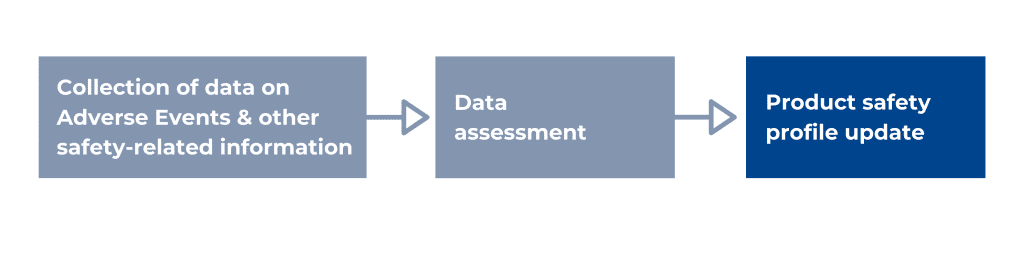

According to the WHO, pharmacovigilance, or drug safety, is the science and activities relating to detecting, assessing, understanding, and preventing adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems. The main responsibilities of pharmacovigilance personnel are the timely collection, recording, and notification, appropriate assessments, and expedited and periodic reporting of safety data. More specifically, a PV system collects data on Adverse Events (AEs), other safety-related information like off-label use, medication errors, overdose, counterfeit products, etc. It assesses this data for causality, seriousness, risk, and risk management options, and based on these assessments, the product safety profile and the labelling can be updated. The interactions between drugs can be considered safe or unsafe, or wrongful prescription of a medication can be identified, etc., and, in more severe cases, a batch or an entire product needs to be withdrawn from the market.

A description of the PV system set-up, the SOPs, and up-to-date PV data are kept in a crucial pharmacovigilance document, the Pharmacovigilance System Master File (PSMF), part of the MAA.

ADR Reporting System

Data about adverse events is typically collected through spontaneous and solicited reports from healthcare providers, pharmacists, and patients/consumers;

A spontaneous report is an unsolicited communication by a healthcare professional or consumer to a competent authority, marketing authorization holder, or other organization (e.g., regional pharmacovigilance center) that describes one or more suspected adverse reactions in a patient given one or more medicinal products.

Spontaneous reports can also be collected through medical and general literature sources, social media, and non-interventional post-authorization studies for which the protocol does not require systematic collection, etc.

On the other hand, solicited reports of suspected adverse events are those derived from organized data collection systems, which include clinical trials, non-interventional studies, registries, post-approval named patient use programs, other patient support, and disease management programs, surveys of patients or healthcare professionals, compassionate use or named patient use.

AE reports are called Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs), and they have to fulfill the four criteria of having an identifiable patient, reporter, drug, and adverse event. To collect ICSRs and data from other sources, pharmacovigilance personnel must have an established network with contacts with healthcare providers, patient organizations, and Competent Authorities (CAs), and therefore be familiar with the local language, regulations, and the relevant national or regional databases.

ADR Coding & Safety Database

The collection of AE data from various sources and regions automatically results in diverging standards and reporting rules. For this reason, harmonization is performed by using standardized coding of ADRs, usually according to the ICH’s MedDRA dictionary (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities). Furthermore, medicinal products can have multiple manufacturers or different brand names in other regions, so they are also coded to improve data accuracy and comparability. Finally, data from each ICSR is entered into a safety database. Many safety databases exist, and choosing the right fit partly depends on local and regional regulatory requirements and the techniques used to collect PV data. We will discuss the aspects that determine the choice for a particular PV database in more detail in a future blog post.

Assessment of Causality, Seriousness, & Expectedness

An adverse event (AE) is any untoward medical occurrence in a patient, or clinical investigation subject administered a pharmaceutical product and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment. Adverse events judged by the reporter or sponsor as having a reasonable suspected causal relationship to the product are qualified as adverse reactions.

Therefore, all spontaneous reports notified by healthcare professionals or consumers (GVP– Module VI) are considered suspected adverse reactions since they convey the suspicions of the primary sources unless the reporters specifically state that they believe the events to be unrelated to the product.

ADR must also be assessed for seriousness. A serious adverse reaction corresponds to any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose results in death, is life-threatening, requires patient’s hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, results in persistent or significant disability/ incapacity, or is a congenital anomaly/ disability or falls into other important medical events (IME list).

Additionally, the expectedness of an adverse reaction shall be determined by the sponsor according to the reference document.

Finally, the frequency of the ADR needs to be established and updated on the product label.

Safety Signal and Safety Signal Detection

According to GVP Module IX, a signal is any information arising from one or multiple sources. This includes observations and experiments, which suggest a new potentially causal association or a new aspect of a known association between an intervention and an event or set of related events, either adverse or beneficial, which is judged to be of sufficient likelihood to justify verificatory action. Safety signals can arise from a wide variety of data sources, including but not limited to the following: safety and clinical trial databases, ICSRs, aggregate review, published literature, Competent Authorities, manufacturing data.

Signal detection refers to the process of looking for and/or identifying signals using data from any source. It should follow a methodology that accounts for the nature of data and the characteristics and type of medicinal product. Signal detection may involve a review of ICSRs, statistical analyses, or a combination of both, depending on the size of the data set and should be well-documented.

Management of signaling focuses on identify risks earlier, delineate them clearer and communicate them better.

It is worth mentioning that not all signals represent risks, and not all signals will require an additional formal regulatory action (e.g., update of the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) after the assessment has been performed). However, the signaling process is crucial to pharmacovigilance as it ensures monitor and control of potential risks.

Safety signals were described more elaborately in a previous blog post.

Risk Management Plan (RMP)

A medicinal product is authorized on the basis that in the specified indication(s) and at the time of authorization, the risk-benefit balance is judged to be positive for the target population. As pharmacovigilance aims to ensure a favorable risk‐benefit ratio for the product, an RMP for every product should be in place. The RMP is a dynamic document submitted at the time of MAA and should be updated throughout the medicinal product’s life cycle. The RMP contains product safety information and risks associated with the medicinal product and the strategies to prevent or minimize these risks (routine or additional measures).

Measures for preventing or minimizing risks include (a.o.) updates of the product label, dear healthcare professional communication (DHPC), educational programs for HCP/patients, and pregnancy prevention programs (PPP).

Reporting to Competent Authorities

The most important component of data and safety monitoring is adverse event reporting and its completeness and accuracy. AE reporting is significant as it provides a greater understanding of the overall safety of each product, protects patients, allows appropriate modifications and improvements in trial protocols and RMPs, etc. Competent authorities and marketing authorization holders should take proper measures to collect and collate all reports of suspected adverse reactions associated with medicinal products for human use originating from unsolicited or solicited sources. The system should be designed to ensure that the collected reports are accurate, legible, consistent, and as complete as possible for their clinical assessment. Inaccurate and/or inadequate reporting of adverse events leads to an incomplete or misinterpreted final AE compilation and statistical analysis. In the EU/EAA and UK, a Qualified Person responsible for Pharmacovigilance (QPPV) is ultimately responsible for the entire PV system and is the contact person for regional authorities. On a national level, Local Persons responsible for Pharmacovigilance (LPPVs) oversees ADR collection and further PV data. Both roles of QPPV and LPPVs help to ensure proper reporting to Competent Authorities. The advantages of QPPV and LPPVs outsourcing are discussed in another blog post.

Regulations and Guidelines for setting up a pharmacovigilance system

The PV system is framed by regulations and guidelines to be compliant and proven to work properly. In a general frame, a regulation is a rule or order issued by an executive authority or regulatory agency of a government. Having the force of law and a guideline is a non-specific rule or principle that provides direction to action or behavior.

The independent regulatory bodies governing PV regulations are the EMA (EU) and FDA (US) and have an equivalent orientation to evaluate the safety and efficacy of products and ensure patient health.

In 2010, the EU adopted legislation to reinforce pharmacovigilance in the territory and was supplemented by further legislation in 2012. EMA then published Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP). The GVPs are continuously updated and provide guidelines for every aspect of a PV system, including ADR collection and analysis methods, PMSF and RMP guidance recommendations for post-authorization studies, etc. The main legal acts are in EU ARE:

- Regulation (EU) No 1235/2010 and Regulation (EU) No 1027/2012 amending, as regards pharmacovigilance, Regulation (EC) No 726/2004

- Directive 2010/84/EU and Directive 2012/26/EU amending, as regards pharmacovigilance, Directive 2001/83/EC.

- Commission Implementing Regulation No 520/2012, which concerns operational aspects of implementing the new legislation.

The FDA has developed policies, procedures, and regulations to implement its Regulatory initiatives and offers similar requirements and guidance since 2005.

Although the regulations between the FDA and EMA are similar, there are subtle differences in requirements. When setting up your PV system, you should be aware of this to design your PMSF efficiently.

For this reason, the ICH designed global guidelines to increase international harmonization and establish common practices for pharmacovigilance; ICH Efficacy Guidelines E2A-E2F. Furthermore, international standards for the Quality Management System (QMS), which is an essential part of the PV system and the product marketing process as a whole, can be found in ISO 9001:2015 Quality Management Systems. Finally, the WHO offers guidance for some aspects of a PV system (such as collecting ICSRs) and provides guidelines for setting up a PV system in general, although this is more relevant for PV systems of national CAs.

Setting up your PV system requires expertise.

Setting up a pharmacovigilance system requires a great deal of expertise in risk management planning, data collection, analysis, and writing/reporting standards. In addition, you need to invest in a safety database and a network of qualified experts with knowledge of the local language, regulations, and resources. If you are wondering how to meet pharmacovigilance requirements for your market authorization applications, working together with an experienced PV service provider with an established network and expertise might be an appealing option.

Discover how ICSR Pharmacovigilance safeguards drug safety for patients.

How individual case study reporting tracks adverse drug reactions and helps ensuring medication safety.

Expert Guidance on PSURs: Ensuring Drug Safety

Why are PSURs important? How do you write a PSUR? Find out all how PSURs and their role in guaranteeing patient safety.

Literature Monitoring in Pharmacovigilance

Incorporating data from medical and scientific literature is a paramount aspect of patient safety. This wealth of knowledge often constitutes a substantial part of the safety profile of medicinal products. From providing insights on potential side effects to shedding...